Cambridge City Council is developing a Making Space for People supplementary planning document (SPD) for Cambridge. It has requested views on its Central Cambridge Vision, Aims and Objectives and Strategies document, which sets out a ‘vision’ for central Cambridge, and the principles and strategies which could underpin the future SPD. This is the response from Smarter Cambridge Transport.

Executive summary

Smarter Cambridge Transport is supportive of the aims and objectives for the Making Space for People Supplementary Planning Document (SPD), but is disappointed to see only abstract commitments to the environment and public health, and no progress on resolving unavoidable tensions in reallocating space between different highway users and uses. As a result, the vision is unclear and inherently conflicted.

The pre-consultation workshops promised a holistic approach, yet this consultation document appears to perpetuate the siloed, piecemeal approach that is failing the city. In this respect, the two years spent to date on this SPD takes us no further forward. How many more years of “review” and “re-appraisal” do we need? Who will determine the briefs? Who will fund them? How will the interactions and conflicts between objectives be arbitrated?

Most importantly, how will the aims and objectives be translated into an action plan? What will be achieved in a reasonable time frame through Section 106 agreements attached to future developments, and what will require dedicated funding?

We have to make big changes now in response to climate and public health emergencies. Some changes will be painful and initially unpopular – with city residents, businesses and visitors in different ways. We need an honest conversation about how we will reduce motor traffic, where we will re-route buses, how we will fund more bus services, where we will provide more cycle parking, and so on.

These are difficult decisions, which require leadership, vision and empathetic engagement with all communities. Citizens’ Assemblies, including that recently run by the Greater Cambridge Partnership, demonstrate that, if people are involved in the deliberative process of considering options and balancing effects, they will often come to more progressive conclusions than if asked simply to react to a proposal.

We urge Cambridge City Council to move swiftly to cultivating imaginative responses to the challenges set out in the Vision, Aims and Objectives document. This is an essential step towards building a coherent and inclusive vision and action plan for the city’s future.

Q2. Have we got the ‘street user hierarchy’ right?

Response category: Comment

Establishing a user hierarchy

The de facto user hierarchy is determined primarily by the density of each mode of traffic. Pedestrians are at the top of the hierarchy on St John St and Fitzroy St, but not on Bridge St, Emmanuel St or Mill Rd. The hierarchy was established in the Core Traffic Area with physical gates (at the southern end of Sidney St) and bollards (now replaced by cameras); and in Fitzroy St and Burleigh St by pedestrianisation.

In almost all other streets, motor vehicles dominate over public and active transport. As this is a deeply established norm, there is relatively little complaint about it. By contrast, conflicts between cycles and pedestrians generate angry and vocal complaint. Ideally of course, every mode would have its own segregated routes, all sufficiently wide to ensure zero congestion. That is theoretically achievable in a new town, but not in Cambridge.

Compromise is unavoidable. People using different transport modes will have to share spaces. It is essential that politicians demonstrate vision and leadership in making and justifying difficult decisions around those compromises.

There will always be some people who are selfish, thoughtless and reckless, but that is not a reason to reject change. It is up to the police and civil enforcement officers, guided by elected politicians, to play their role in keeping people safe.

Defining a user hierarchy

The intended hierarchy must be specified for each street. Policies are needed on all aspects of street function and design, tailored to typical usage and the physical realities of suboptimal widths and access requirements (e.g. for shop deliveries and emergency services). Street layout, features, furniture, access permissions/restrictions and their enforcement must all align with the policies.

The user hierarchy depicted in the consultation document is generally correct, but omits details that matter.

- What are the ‘specific’ service and delivery vehicles?

- Where do these road users feature?

- Users of mobility scooters (4pmh and 8mph)

- Users of wheelchairs

- Blue Badge drivers

- Taxis (hackney carriages and private hire)

- Private coaches

- Mopeds and motorcycles

- Different sizes of buses (double-deckers to minibuses)

- Where in the hierarchy does green space (trees, verges, hedges, flowerbeds) feature? The green space beyond the asphalt can serve many functions:

- sustainable drainage reduces flooding from heavy rainfall;

- trees provide shelter from rain;

- trees provide shade from sun, significantly reducing ground level temperatures in the summer;

- trees and shrubs create a pollution and noise barrier;

- locally appropriate vegetation provides a habitat for healthy biodiversity;

- attractive landscape significantly increases people’s willingness to walk or cycle.

- Where do the following feature?

- Taxi ranks

- On-street parking (long-stay, short-stay, residents, Blue Badge, coach)

- Loading bays

- Where does street furniture feature?

- bus shelters

- electric charging points

- cycle stands

- cycle lockers

- benches

- public bins

- utility cabinets

- air quality monitoring stations

- planters

- bollards

- lampposts

- telegraph poles

- signposts

- ‘safety’ railings

- Where do movable items feature?

- commercial bins

- domestic bins

- advertising boards

- fly-parked cycles and scooters

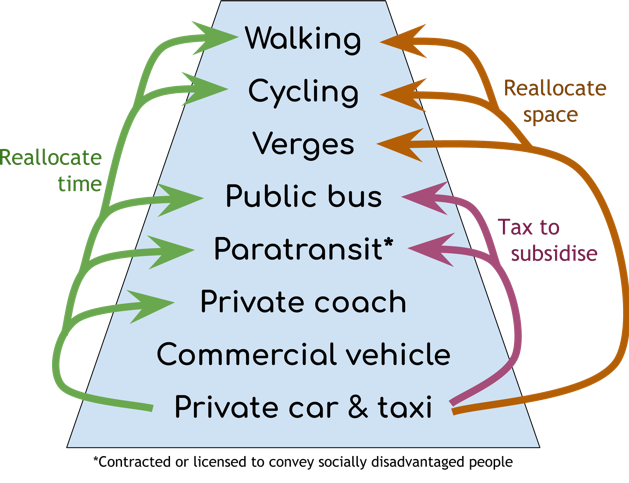

We offer a refinement of the essential hierarchy in Figure 1, which expands on the categories of public transport’ and adds ‘verges’ (which refers loosely to all green space, as described above). It also includes actions required to realise and sustain the urban transport hierarchy.

We do not regard taxis as public transport, and see no reason to privilege them over other private cars. The sole exception is when they are carrying a disabled person, when the same privileges that apply to Blue Badge holders should apply.

Figure 1: The urban transport hierarchy and how policies must act to make it a reality

Q5. Do the strategies cover the right themes?

Response category: Comment

Environment and public health

References to climate change, biodiversity and air quality are much too weak. The first two are existential threats to the human race and most other species on the planet; the third is known to be killing and incapacitating people now.

There should be specific strategies (i.e. implementation plans) for:

- de-carbonising the city, especially transport

- eliminating toxic pollutants

- increasing physical activity to reduce obesity-related illnesses

- increasing biodiversity in the city

- increasing resilience to extreme weather and flooding

The consensus view from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is that every effort is needed to minimise greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. The faster we act, the lower the risk that global warming will pass a tipping point of highly unpredictable runaway climatic and ecosystem changes. National policy has yet to catch up, but the statutory commitment to de-carbonise the UK economy by 2050 is a clear signpost.

Every policy about how people live, work and move about must contain a golden thread of reducing carbon emissions. That translates loosely to reducing energy consumption (until such time as we have replaced the 80% of national energy consumption derived from fossil fuels with carbon-free alternatives).

Transport-related strategies

All transport modes are covered and the objectives are reasonable. However, there are no details on how any of the objectives will be achieved and, most importantly, what compromises will be considered, given limited space and money.

S1 Make the Central Cambridge easier to navigate so that everyone gets the most out of their visit or trip by providing better signage and designing for legibility.

What, other than improved signage, is being proposed for consideration?

S2. Extend the pedestrian focused area to create a comfortable walking pace and accessible environment that reduces conflict between cyclists and pedestrians.

What geographical area should be considered for expansion of the “pedestrian focused area”? What access should cycles have? What infrastructure could be used to segregated different modes? Will taxis and buses continue to traverse “pedestrian focused areas”?

S3. Create facilities for cyclists who want to pass through the city centre so they have a choice to use faster, safer routes that avoid the busiest streets.

How will S3 be reconciled with S2?

S4. Provide cycle routes to, and parking within the city centre and at local centres informed by a review of cycle parking facilities and locations that addresses high demand and support active travel options.

How will this be reconciled with S2? What locations count as “local centres”? What counts as “high demand”? What locations will be in scope for re-purposing space for cycle routes and cycle parking? What budget will be made available for any building work?

S5. Re-appraise the location and function of central car parks and access to and from them to minimise impacts on the enjoyment of the city centre for pedestrians and cyclists and the reliability of bus journeys.

What could a re-appraisal of the location of central car parks conclude (given relocation is almost certainly out of scope)? Why is a re-appraisal necessary when good data on traffic and car park usage is already available? If a reduction of car parking provision is being considered, what provisions are being considered to replace lost income to the City Council?

S6. Re-appraise bus and coach (public and tourist) routing and the location and function of stops and drop off points to minimise impacts on the enjoyment of the city centre whilst maintaining or where possible improving access into the city centre.

What new routes for buses and coaches are being proposed for consideration? What new locations for bus stations/interchanges and coach drop-offs?

S7. Review routing and arrangements for delivery and service vehicles to minimise impact on city movement and enjoyment of the city for pedestrians and cyclists.

What new routes and arrangements for delivery and service vehicles are being proposed for consideration?

S8. Review the role, facilities and locations of taxi stands to minimise impact on city centre movement whilst maintaining good accessibility. Also review routing of private hire vehicles across Central Cambridge.

What options for taxis are being proposed for consideration? There should be specific mention of EV charging points as one of the facilities at taxi ranks and elsewhere in the city.

S9. Create opportunities to reallocate space freed up by reductions in motor vehicles to create new and repurposed public spaces.

Which spaces are being proposed for consideration?

S10. Enhance existing and new public spaces by creating opportunities to dwell including places to stop, sit and relax.

How will S10 be reconciled with S3 and S4?

Cycle parking

Modal shift from driving to cycling requires secure, convenient cycle parking everywhere. The number of cycle parking spaces available needs to grow ahead of the rate at which modal shift is desired. Fly-parking of cycles on pavements is undesirable because it obstructs people walking, in wheelchairs and mobility scooters, or pushing children’s buggies.

Provision at scale in the city centre and central railway station requires dedicated, multi-storey, cycle parks. The city will soon outgrow the cycle park at the railway station (Utrecht, with approximately double the population of Cambridge, recently expanded cycle parking provision at its railway station to 12,000 spaces; Cambridge station has around 2,800 spaces.)

These cycle parks need to be designed to accommodate bicycles, tricycles, cargo bikes, bikes with trailers and hand cycles. There need to be charging points for e-cycles (with and without removable batteries); and secure lockers for cycles, cycle kit and temporary storage of luggage and shopping.

Multi-storey car parks and other public buildings with large basements may offer the best spaces to house thousands of cycles securely. However, multi-storey car parks also provide a large income to Cambridge City Council (£10.1m in 2017/18). So, converting car parking to cycle parking spaces has an ongoing cost implication that will need to be addressed. Management and supervision of cycle parks is essential to ensure people’s safety, deter theft, and avoid racks getting clogged up with abandoned cycles. That entails additional cost.

As cycling is a public good with negligible external costs, and is a significant contributor to de-carbonising transport, provision of cycle parking should continue to be free at the point of use. Funding options for infrastructure, including secure, monitored cycle parking, will need to be explored. Possible sources of funding include increased car parking charges and a Workplace Parking Levy. The Dutch model of charging to park for more than 24 hours could raise a small revenue and would assist with managing usage (deterring long-term storage and making it easy to identify abandoned cycles).

In the early years, the recurring funding requirement to cover loss of revenue from converting one or two hundred car parking spaces to cycle parking would be small since multi-storey car parks are rarely all full (typically on a few weekends in November and December). Longer-term, a larger funding stream will be required.

The Queen Anne Terrace car park could be an ideal location for a large cycle park and hire centre, with easy connections to and from buses to all parts of the city (see Bus routing below).

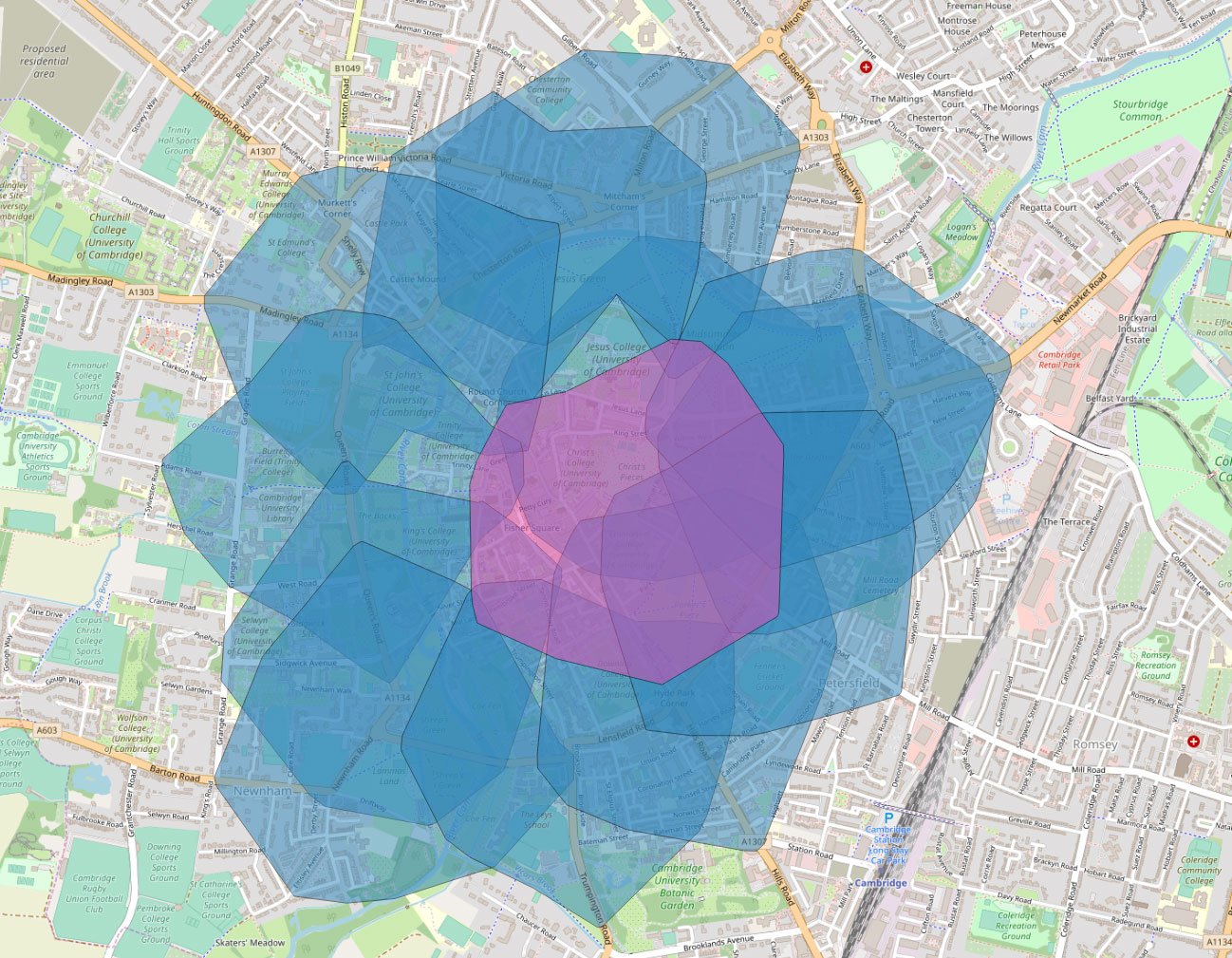

Bus routing

The central hub comprises a bus station with 11 bays, and another 15 dispersed around the surrounding streets in six locations (see Figure 2). (The bus stop on Emmanuel Rd is included because it is the most central stop for the Busway A service; the ones on Parkside are used by the X5 Oxford–Cambridge and National Express intercity services.) Interchanging can involve a walk of up to 600m and crossing roads without designated, let alone controlled, crossing points. There is no central information point and no signage to guide people to the right stop.

Figure 2: Locations of the 27 city centre bus bays. Circle diameter is 520m. (Map © OpenStreetMap)

Many buses are routed to and from the central hub via narrow streets, bounded by historic buildings, including Magdalene College (started in the 15th century), Round Church (started in the 12th century), St Botolph’s Church (started in the 14th century), Queens’ College Old Hall (started in the 15th century) and Christ’s College (started in the 15th century).

Buses sweep over pavements at corners, obstructing pedestrians and making them – especially those with impaired vision – feel unsafe. In several locations, people cycling have to wait or get on the pavement to let an oncoming bus pass (see Figure 3). Pollutants (especially particulates and nitrogen oxides) build up in narrow streets, exposing people to dangerously unhealthy concentrations. The weight and vibrations caused by 15 tonne buses damage the roads and surrounding buildings.

Figure 3: Bus routes through the centre of Cambridge. Red circles indicate areas of conflict with people walking and cycling. (Map © OpenStreetMap)

Future growth in population, mainly in settlements beyond the green belt, and in employment sites around the city will require a large expansion in the frequency and coverage of bus services into the city – potentially tripling inside ten years. The current bus hub has little capacity to absorb that growth, and more buses in the city centre would further degrade people’s experience of walking and cycling in the city.

What are the alternatives? Hubs have an essential role in enabling people to interchange. It’s not possible to run public transport services from every village and suburb to every destination (employment site, school, shop, leisure facility, etc.) So, the success of public transport is largely dependent on making it easy and intuitive for people to complete a journey with a change of mode or vehicle, e.g. walk → bus → bus → walk, or cycle → train → bus → walk.

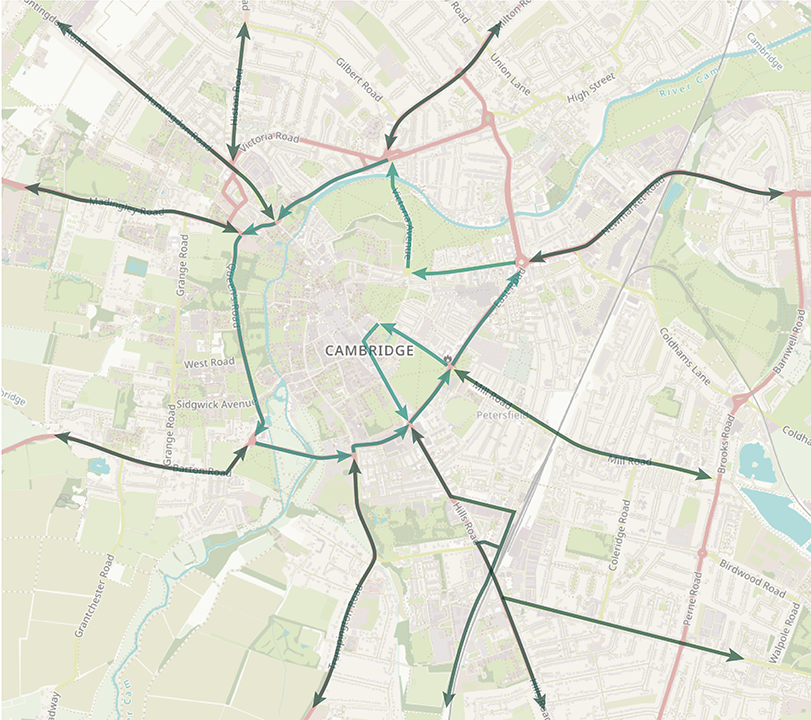

One option is to route buses around the inner ring road following a ring-and-spoke or ‘lollipop’ routing pattern (see Figure 4). This could work well in Cambridge because there is an inner ring road close to the city centre. The most intuitive way to run buses is counter-clockwise, so that doors open towards the city centre. Some buses would still enter the city centre via Parkside, Emmanuel St and Regent St (e.g. a frequent shuttle service between the city centre, Cambridge station and the Biomedical Campus). A small fleet of electric minibuses (see Figure 5) can assist people in moving around the city centre and connecting with rural and suburban services.

Figure 4: ‘Lollipop’ routing of buses around the inner ring road

Benefits include:

- To reach any destination in Cambridge requires at most one change of bus anywhere on the inner ring road.

- To interchange between buses entails walking no further than the length of two bus bays, and does not require crossing a road.

- More of Cambridge would be within easy walking distance of a high frequency bus service, making bus travel attractive to many more people in the city. This reduces car traffic and increases demand, and hence revenue, to run the buses.

- Removing bus – and potentially all large vehicles – from the city centre opens up opportunities to widen pavements, add cycle lanes, and pedestrianise more of the city centre.

- Many streets would see a renaissance, either because they become more attractive places to be (e.g. Bridge St, Silver St, Hobson St, King St and Round Church St) or to get to (e.g. the Grafton Centre, Sun St, Mitcham’s Corner and Chesterton Rd).

There are however some disadvantages that need to be taken into account:

- Bus turn-around time (between reaching the inner ring inbound and leaving it outbound) may be slower than going in and out of central Cambridge. This makes services slightly less cost efficient compared with now. However, the comparison should be made with a “do nothing” scenario, in which the city centre becomes increasingly congested for buses.

- Bus drivers need to lay over at the outer end of their route rather than in central Cambridge. However, there could be layover facilities around the Grafton centre, e.g. on Sun Street.

Queen’s Rd and The Fen Causeway will carry many more buses than they do now.

More detail may be found at https://www.smartertransport.uk/cambridge-city-bus-hub/

Figure 5: Small electric minibuses operate in Ghent city centre

Bus stops

There is no mention in the SPD of bus stops or shelters. There needs to be a programme of reviewing the locations of bus stops, and the appropriate facilities for each one:

- Shelter

- Lighting

- Real-time passenger information display

- WiFi

- Secure cycle parking nearby

- CCTV and a 24-hour help intercom (where security is a concern)

Car-Free Days

Car-free days are a well-established way for places to experience the benefits of transferring street space to people, without the dangers and pollution caused by motor vehicles. The Mill Road Winter Fair is a good example of this on a small scale. The Combined Authority and County Council should actively support car-free days, reducing bureaucracy and expense to the minimum.

World Car Free Day is held annually on the 22nd September (the City Council may prefer its first car-free day to be on a Sunday). Similar movements exist under different names, e.g. the Open Streets Project in North America, and Ciclovia in Bogotá and Belfast.

Add comment